The two-hour Prague Communism and Nuclear Bunker Tour promised a hands-on introduction to the city’s Communist past. A visit to an underground bunker built during the Cold War added a fascinating layer of interest to the experience.

Walking tour

The walking tour started in Prague’s Old Town. The first hour was consumed with pausing beside various landmarks with connections to the theme of the tour.

One of the early stops was beside a plaque commemorating the start of the Velvet Revolution. The open palms indicated the protestors carried no weapons, and the universal sign of two fingers represented peace. The bloodless revolution in Czechoslovakia in 1989 led to a return to democracy after 50 years of Nazi occupation and Communist rule. It paved the way for the formation of the Czech Republic and Slovakia four years later.

The above-ground commentary brought to life my previous exposure to studies of the Cold War. It was a tantalizing introduction to the highlight of the tour — a descent into an underground bunker.

Prague Nuclear bunker tour

Most bunkers built in the 1950s have been neglected and are no longer safe to enter. The one used by the tour company is under the Parukarka Park in the Žižkov district in Prague 3, a few kilometres from the Old Town. We travelled by tram to a neighbourhood dominated by drab concrete tower blocks and a Soviet-era communications tower known as the second ugliest building in the world.

Colourful graffiti camouflages the entrance to the bunker.

Accessible only though a guided tour, the bunker required a formidable set of keys to gain entry.

The blast steel door weighed four tonnes and appeared to be about eight inches (20 centimetres) thick.

We descended 16 metres down a spiral staircase, about four floors, to a labyrinth of narrow passageways and small rooms.

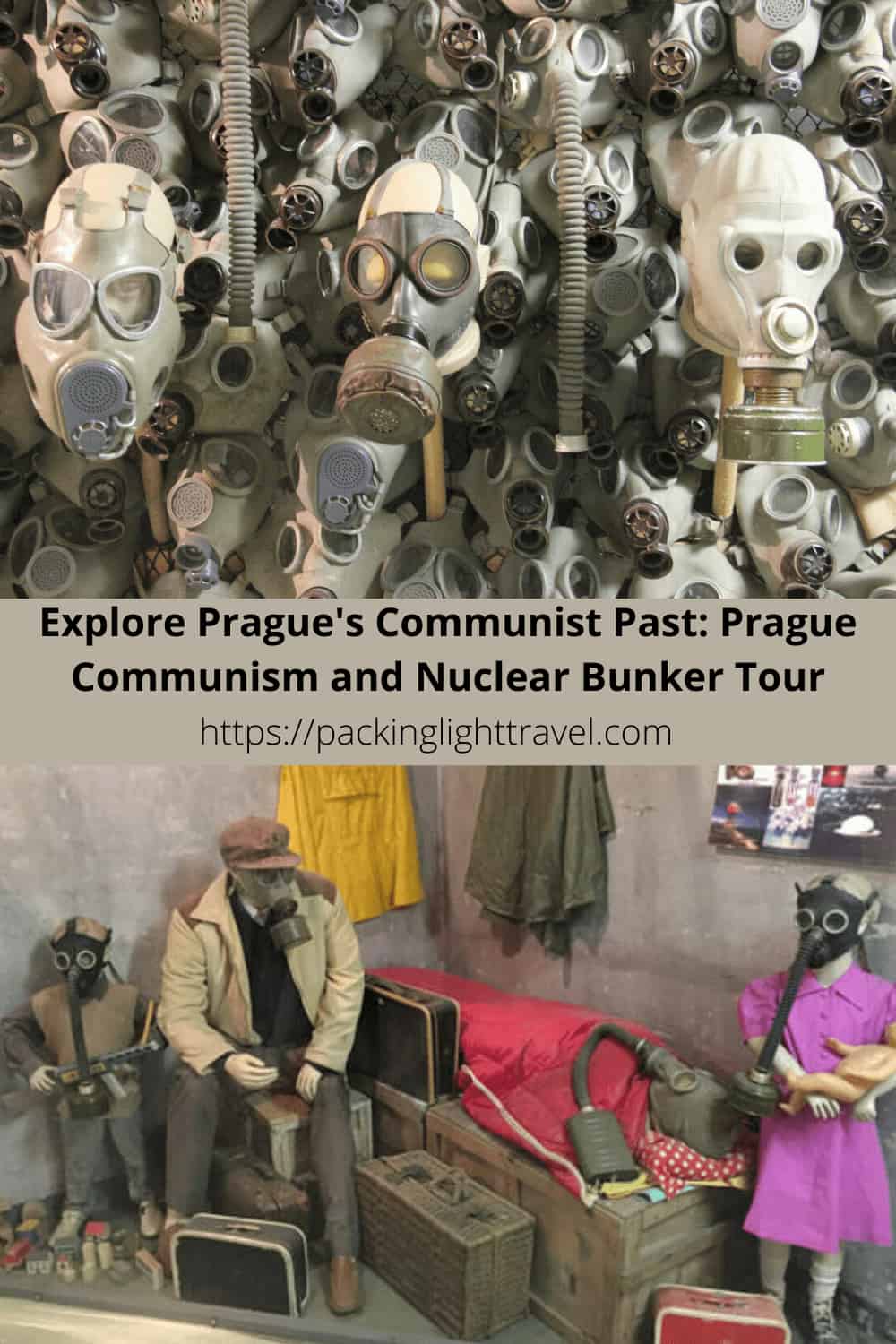

The tour explored about twenty per cent of the bunker. Original estimates were that 5,000 people could shelter from a nuclear apocalypse, with each person assigned an unrealistic half square metre of space for a maximum of two weeks.

Folks needed to be prepared with an evacuation suitcase, a radio and extra batteries, and a two-week supply of food to take to the bunker at a moment’s notice. I figure most of those suitcases would have taken up the requisite half square metre.

In such a harsh environment (and a catastrophic one above ground), the bunker architects considered anti-suicide measures in the design. Toilet cubicles were made of wood, with a curtain for a door. The flush chain was short, and mirrors were not made of glass.

The bunker was a rich repository of cold-war memorabilia. There were books, newspapers, posters, medals, assorted military equipment, and photographic displays of key events of the Communist era.

The equipment seemed primitive and not up to guaranteeing a person’s survival of a nuclear holocaust. Thank goodness none of it was tested during the Cold War. The first and last atomic weapons used in warfare were detonated over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II. It seems that the fear of nuclear war prevented it; still, countries such as Czechoslovakia invested in infrastructure and equipment, just in case. But I suspect that this was less about protecting citizens and more about feeding an agenda of propaganda against the West.

On display were endless variations of gas masks.

Whole-body versions were available for small children.

Another corridor took us to a display of a decontamination room where two white-rubber-suited mannequins scrubbed down a naked mannequin with brooms. I can’t imagine the process was at all effective.

Our guide Katarina explained that the average young Czech knows very little of the Communist era. There’s a vast gap in the school curriculum between the end of World War II and the return to democracy in the early ‘90s. If I understood her correctly, Czechs are divided on the 40 years of Communist rule. Hence, no official version of that period exists.

The tour ended in Wenceslas Square, where Jan Palach, a university student, committed suicide by self-immolation in a political protest outside the National Museum. It followed the 1968 invasion by the Warsaw Pact armies of 500,000 troops and 6,300 tanks, ending the Prague Spring reforms introduced under the leadership of Alexander Dubček. Palach’s compatriot, Jan Zajíc, followed Palach’s example a short time later.

The verdict

I thoroughly enjoyed the tour. Our guide Katarina was obviously born after the Velvet Revolution. Still, she was able to weave the experiences of her parents into the narrative. It was an informative and fascinating tour.

Care to pin it for later?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks