Updated January 1, 2018

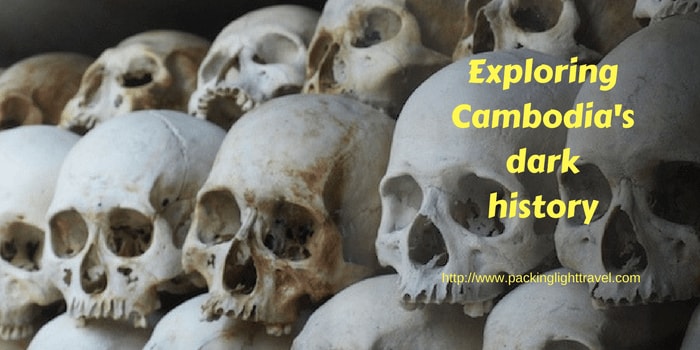

Do you include dark tourism in your travels? If you’ve visited the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, Auschwitz in Poland or the 9/11 Memorial in New York City, you’ve engaged in dark tourism. ‘Dark tourism’ describes travel to places historically associated with death and suffering. In Cambodia, there are two places in particular that have a ‘darkometer’ rating of 10. This is the “deepest darkest of the dark” rating assigned by Peter Hohenhaus of Dark Tourism. For better or worse, they’re a powerful combination for exploring Cambodia’s dark history.

Khmer people: First impressions

Describing my experience wouldn’t be complete without sharing my first impressions of Cambodians. It was very strange. I developed this almost instantaneous admiration for these warm, friendly, and peaceful people. I shared the streets and markets with people who seemed to work day and night to feed their families. Quick to flash a smile, offer service, or engage in conversation, they seemed to have outwardly rebounded, both in population and spirit, from their brutal and tragic history.

I found myself looking into the faces of older Cambodians. I couldn’t help but think that anyone born before 1979 had been through unimaginable hell. Given Cambodia’s dark history, those faces were definitely in the minority. In fact, people aged 55 or more make up just 9.6% of the population. In Germany and Japan, it’s 36% and 39% respectively.

I wanted to learn more about Cambodia’s genocidal past. Having a deeper understanding of the impact of the atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge felt like an important piece of a visit to Cambodia. As a result, I decided to tour S-21 (Tuol Sleng) in the heart of Phnom Penh, and The Killing Fields (Choeung Ek) on the outskirts of the city.

Exploring Cambodia’s dark history

1. Khmer Rouge

Exploring Cambodia’s dark history requires an understanding of factors that led to the emergence of the Khmer Rouge.

By 1975, Cambodia had become a terrifying place to live. Between 1965 and 1973, the United States dropped 2.75 million tons of bombs over Cambodia to disrupt supply lines to their enemies in Vietnam. To put this into perspective, the Allies dropped just over 2 million tons during all of World War II. In effect, Cambodia may be the most heavily bombed country in history. As a result, as many as 800,000 Cambodians perished. This contributed to driving an embattled populace into the hands of an insurgency led by Pol Pot’s Communist Party of Kampuchea (Khmer Rouge).

The true nature of Pol Pot and his ideology soon became clear. The Khmer Rouge evacuated cities in an attempt to convert Cambodia to a Maoist agrarian society. In Phnom Penh alone, the city was emptied of its entire population of 2.5 million. People were forced to work in farm labour camps. All industry stopped. Books were burned and religion was outlawed. The local currency was abolished. Foreigners were expelled. Schools and newspapers were shut down, and ownership of private property was forbidden.

2. Tuol Sleng Museum of Genocidal Crime (S-21)

Smaller interrogation centres were scattered across Cambodia, but S-21 was by far the largest. From the outside, it looks like the ordinary school it once was.

Inside are weapons of torture, and photographs of people who were murdered.

Classrooms were converted to tiny prison cells, mass detention areas, and interrogation rooms. The upper balconies were covered in barbed wire to prevent prisoners from jumping to their deaths.

Like the Nazis before them, the Khmer Rouge were meticulous in their record keeping. They took photos of every new detainee. Detailed ‘confessions’ of tortured prisoners were retained. I found myself staring at the photographs of detainees, imagining their only crime being that they wore glasses or spoke more than one language. I wondered if they were aware of the fate that awaited them. In their faces, I saw a resemblance to those I’d seen on the streets of Phnom Penh. Given how many people died, every family must have lost loved ones. I imagined how overwhelming it must be for any Cambodian who visits a museum or monument documenting the brutality of the Khmer Rouge.

Of S-21’s 20,000 or so inmates, only 7 survived. The victims were mostly ordinary Cambodians. However, some were former Khmer Rouge who became victims of the regime’s systematic and paranoid internal purges.

3. Choeung Ek: The Killing Fields

Choeung Ek is one of the estimated 500 killing fields found throughout Cambodia. This former orchard and Chinese cemetery is about 15 kilometres from the heart of Phnom Penh. Between 1975 and 1979, as many as 20,000 men, women, and children were transported during the night by truck from S-21. Choeung Ek became an extermination centre and mass burial ground.

Mass graves containing 8,895 bodies were exhumed after the fall of the Khmer Rouge regime.

However, 43 of the 129 communal graves have been left untouched.

A walk through the quiet grounds yields scraps of clothing or the odd tooth or bone fragment underfoot.

These are moving reminders of the atrocities committed here just a few decades ago.

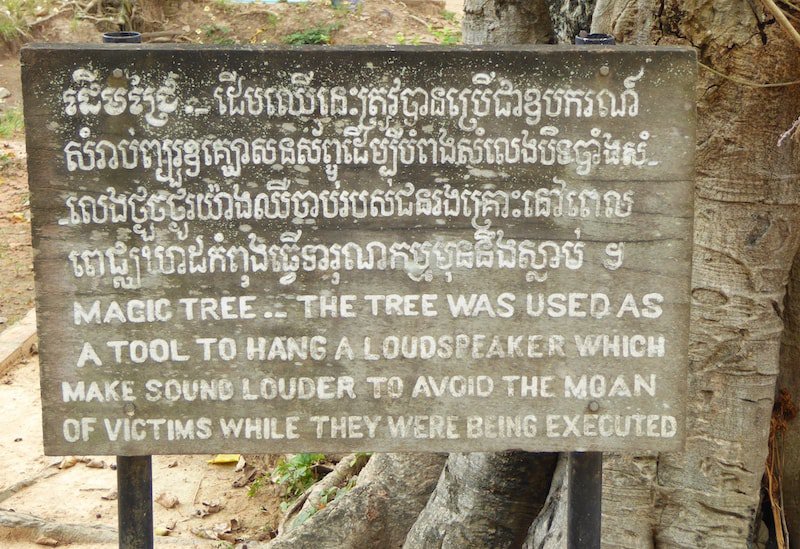

Most people were bludgeoned to death to avoid wasting precious and costly bullets. Torture and killing instruments are on display in an on-site museum.

Children, infants, and babies were killed when their heads were smashed against the Chankiri (Killing) Tree.

The thinking behind this madness was that the youngsters wouldn’t grow up to exact revenge for the fate of their parents. Some of the soldiers laughed as they beat the children’s heads against the tree. Not to laugh could have indicated sympathy or regret, making them a target of internal purges.

Beside the Killing Tree is a Spirit House, a dwelling place for spirits that have not found rest. Buddhist tradition requires exacting rituals associated with death. If not, the deceased will not be able to move to the next stage of the life cycle: rebirth. The fact that these traditions weren’t followed during the genocide is a continual source of suffering for surviving family members.

Today, Choeung Ek is a memorial, marked by a Buddhist stupa. The stupa is filled with more than 5,000 human skulls. Many have been shattered or smashed, evidence of the manner of death and barbarism of the Khmer Rouge.

An audio tour with an accompanying pamphlet is included in the modest entrance fee. It contains stories by those who survived the Khmer Rouge era. There’s also a chilling account from a Choeung Ek executioner describing some of the killing methods. The audio tour allows visitors to move at their own pace and pause frequently for individual reflection. It helps make The Killing Fields a very powerful experience.

What to expect

Expect to be moved by exploring Cambodia’s dark history.

- If your experience is anything like mine, prepare to be stunned into silence. You’ll visualize the atrocities that took place, and likely shed tears for those who perished.

- You might imagine what Cambodia could have been like today if such an enormous slice of human potential hadn’t been obliterated.

- Expect to wonder how in creation these, and other crimes against humanity, could happen on such a catastrophic scale. You’ll oscillate between sadness and incredulity at the sheer senselessness of it all.

- More recent examples of genocide in Rwanda, Syria, Iraq, and Myanmar might invade your thoughts. It can feel overwhelming.

- Did these atrocities happen during your lifetime? If so, expect feelings of regret and anger that they took place while the world stood by. That was my experience. As a twenty-something exploring the world, I was largely oblivious to what was happening in Cambodia.

- Were you unaware of the genocide before arriving in Cambodia? If so, you might want to question why this is the case.

- You may even question the appropriateness of dark tourism. A parade of tuk-tuks and tour buses disgorge camera-wielding tourists. The key difference between these and other tourist attractions is that S-21 and Cheoung Ek are frightening and morbid places. Does your presence assault the memory of those who died? Or, are they important sites for education and change? You’ll likely wonder what other visitors are thinking and feeling, and if and how they’ll be changed as a result.

Why visit S-21 and Choeung Ek?

Is it appropriate to travel to such dark places of human tragedy?

I think it’s very important to do so. Why?

- It’s a way to show respect for those who perished, and for the ones who escaped with their lives.

- It stimulates reflection. It’s the kind of reflection that has the potential to engage people in human rights issues. It encourages us to become more curious and informed travellers and global citizens. These kinds of sites can be powerful catalysts for change.

- They encourage us to think about foreign policy and international relations, and their impact on the lives of ordinary men, women, and children. For example, many historians believe the U.S. bombing campaign drove many rural Cambodians into the arms of the radical ideology espoused by the Khmer Rouge. This paved the way for a madman such as Pol Pot to assume power.

- They remind us that meddling militarily in other nations’ territory or affairs creates instability. Instability produces the conditions for insurgencies and fanaticism to take root. Both are capable of unleashing horrific effects. For a more recent example, we just need to look at the brutality and barbarism of ISIS/ISIL. It was the invasion of Iraq and the disbanding of the Iraqi military that spawned the growth of al Qaeda and the splinter group ISIS (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria).

- S-21 and Choeung Ek stand as compelling reminders of what can be learned from Cambodia’s genocidal past. If they inspire activism, the world will be better for it. There are lots of small, and not-so-small, actions we can each take to put an end to genocide once and for all.

Getting there

Hire a tuk-tuk. A tuk-tuk is a two-wheeled carriage pulled behind a motorcycle. It typically carries up to four passengers. It’s an inexpensive form of transportation. You travel slowly enough to absorb the surroundings and feel the pulse of a place.

I stayed in a hostel in Phnom Penh. Our driver, Boray took us across town to S-21, then out to Choeung Ek before returning us to the hostel. I recommend this order, but perhaps spreading your visits over two separate days.

Drivers wait while passengers tour each facility. The journey took a little more than half a day, and cost 15 USD. Hostels are great for meeting up with others. In this case, I shared the ride and the cost with Carolina from Colombia, Cyril from France, and Kari from Norway.

A follow up to my 2014 visit was in 2017. I was visiting my niece in Phnom Penh who introduced me to Ming and Sreyoun. They learned of my interest in the genocide and agreed to meet. I was concerned that heightening my awareness shouldn’t be at their expense, but they were willing to share their memories. They described the forced march to the countryside, and the murder of loved ones. Their grief, after all these years, was palpable. I couldn’t help but wonder how many generations it will take for the pain to dissipate. Understandably, neither has visited S-21 or the Killing Fields.

Before your visit

To help evaluate a decision to visit Tuol Sleng or Choeung Ek, or other dark-tourism sites, the article, What is dark tourism and can it ever be ethical? by The Travel Psychologist highlights several benefits and pitfalls. It also offers useful advice as you prepare to do so.

Prior to your visit, take a look at The Killing Fields. The 1984 film is based on the experience of Cambodian photojournalist Dith Pran who coined the term ‘killing fields’ after his escape during the genocide.

Read Loung Ung’s stirring account of her life under the Pol Pot regime in First They Killed My Father: A Daughter of Cambodia Remembers. It’s a powerful reflection on her experience as a child during this period of Cambodia’s dark history. A film of the same name was released in 2017.

If you found this post useful, please share it by selecting one or more social media buttons. Have you visited these sites? If so, what was your experience? If not, perhaps you have other thoughts? Or, have you visited other dark-tourism sites that were moving experiences? I’d love to hear from you in the comments. Thank you.

Might you be interested in two other posts on Cambodia? If so, check out Cycling in Cambodia and Cambodia’s Ta Prohm: Angkor’s jewel.

Pin it for later?