Updated May 1, 2023

During the pandemic when travel as we knew it felt like a remnant of the past, I found myself reflecting on my early international travel experiences. Musing involved three questions. What was it like to travel in the 1970s? What’s better? Then or now?

Table of Contents

- Highlights of travel in the 1970s

- What was it like to travel in the 1970s?

- 1. Europe was on our radar

- 2. Five weeks on a ship to get to Europe

- 3. It involved at least a year or two of travel

- 4. Smallpox vaccinations weren’t pleasant

- 5. We lived with lots of other travellers

- 6. It was a time of a political awakening

- 7. Travel plans took time to unfold

- 8. Visas took time to get

- 9. Mass tourism didn’t exist

- 10. Paper plane tickets were the norm

- 11. Not all ferries were the roll-on-roll-off variety

- 12. Travel guides were limited

- 13. Plans were loose and changeable

- 14. Travelling companions were collected along the way

- 15. Book trades were a social endeavour

- 16. The UNESCO World Heritage List didn’t exist

- 17. Travel quashed preconceived ideas

- 18. Tea and biscuits were staples

- 19. Conversation was key

- 20. Several address books were filled

- 21. Country-counting wasn’t a thing

- 22. A tour with no guarantees of reaching the destination

- 23. We survived on a limited travel budget

- 24. We survived without Facebook and Instagram

- 25. Water wasn’t packaged in bottles

- 26. Poste Restante figured prominently in our plans

- 27. Aerogrammes and postcards were communication staples

- 28. Telephone calls were rare

- 29. Passport stamps were important

- 30. A divided Europe

- 31. A divided Germany

- 32. Taking photographs required constraint

- 33. The underground market expanded travel budgets

- 34. For the most part, airport security didn’t exist

- 35. Jumping freight trains was possible

- 36. We were out of touch with world news

- 37. Travellers’ cheques came with challenges

- 38. Journalling was a daily event

- 39. Music wasn’t accessible on the road

- 40. Lifelong friendships were formed

- Which is better… then or now?

Highlights of travel in the 1970s

My international travels began with a five-week voyage across two oceans from Australia to the United Kingdom, and by the end of the decade, I’d settled in Canada.

Much of it was of the independent variety dominated by limited planning and shoestring budgets. Tours weren’t part of the picture. Hitchhiking was common, and jumping freight trains, although enjoyable, less so. Travel by motorcycle and an endless string of Volkswagen Kombi vans were popular choices of the time.

What was it like to travel in the 1970s?

1. Europe was on our radar

From Australia, Europe was an obvious choice as a travel destination. Asia, while closer, wasn’t as popular. Until Australia’s White Australia policy was finally abolished in 1973, it was one of the cornerstones of the country’s approach to immigration. Unfortunately, its underlying assumptions about race and ethnicity were embedded in its citizens’ perception of its neighbours.

Much of Asia was viewed as a place of poverty, danger, and political instability. The American War in Vietnam was raging, and the cultural familiarity of Britain, with its easy entry requirements, made it a more popular destination for young Australians and New Zealanders from the antipodes. Our self-imposed limits on attractive travel destinations were propelled by Eurocentric perceptions and values.

2. Five weeks on a ship to get to Europe

In 1972, a one-way ticket from Australia to Britain cost AUD 400 by air or sea (in a six-berth cabin from Sydney on the SS Australis). According to the Australia Inflation Calculator, that was valued at AUD 4,250 in 2020. To a 22-year-old, the choice was a no-brainer. Five weeks of room and board and six ports of call in six countries was the way to go. Those 9-cent beers and endless partying had nothing to do with it.

3. It involved at least a year or two of travel

When did the gap year become a thing? It wasn’t a factor in my choices, or those of any of the travelling friends I had the good fortune to accumulate along the way. We finished high school, chose a vocation that usually involved post-secondary studies, worked for two or three years, and saved enough money to travel for an extended period.

Before deregulation of the airline industry in the late ‘70s, air travel was expensive. Once fares were no longer set by governments and airlines no longer had monopolies on routes, it opened up travel to the average person. Until that happened, Europe was expensive to reach so it wasn’t a destination to contemplate for a short period.

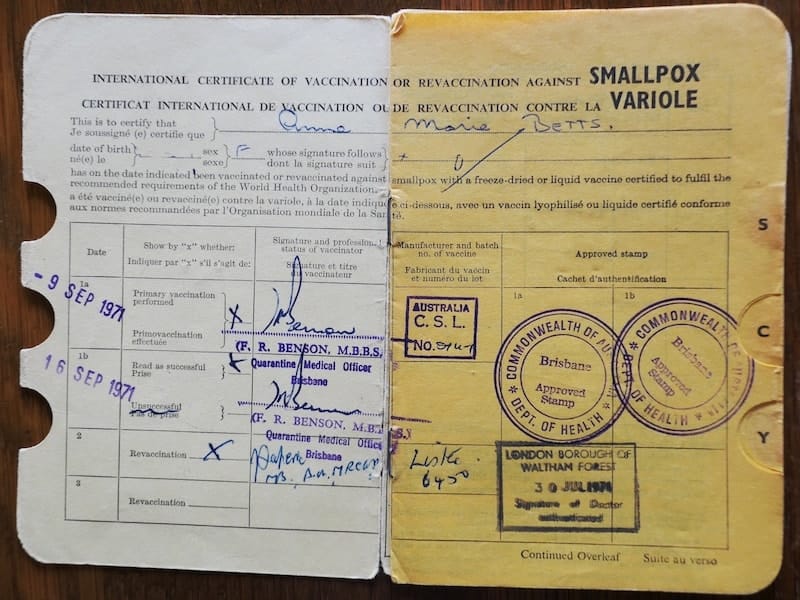

4. Smallpox vaccinations weren’t pleasant

After 3,000 years of human infection, smallpox was finally declared eradicated in 1979. Until then, it was the world’s most feared disease. In the 20th century alone, it’s estimated to have claimed 300 million lives. The thirty percent fatality rate was part of the story. The other involved the potential loss of eyesight and the painful development of pus-filled lesions followed by pitted scars.

In 1971, the prevailing recommendation for international travellers departing Australia was to be vaccinated against smallpox, cholera, and typhoid. Because the smallpox vaccine left behind a distinctive scar, many people chose the inside of the arm by the elbow for the site of inoculation. That was my choice. I recall keeping my arm outstretched for several days to avoid bumping the ugly pus-filled lesion and subsequent scab.

5. We lived with lots of other travellers

By the time the SS Australis berthed in Southampton in February 1972, my group of potential flatmates numbered seven. While crossing the Atlantic, we had agreed to look for a flat together in London and share accommodation and living costs until the summer.

After summer travels, our group expanded to ten the following winter. In our flat in the Stamford Hill area of London, we’d each contribute our share of the rent and food costs to a jar in the pantry, in cash.

Most of the women were teachers who finished work earlier than the guys so delineation of tasks associated with shopping, cooking, and doing dishes were structured along gender lines. The women shopped and cooked, and the men took care of cleaning up after the evening meal. With ten mouths to feed, and lots of drop ins, picking up supplies required planning and coordination.

Before the Covent Garden market became the trendy place it is today, fresh produce was sold by the box or sack, much of it from the backs of farmers’ trucks and lorries.

We lived in close quarters, with only one bathroom. I have no recollection of drama or conflict. There were no cliques. We depended on each other for camaraderie, friendship, social interaction, and ability to keep to a budget. Our social tentacles reached into ten different workplace circles. Conversation was never lacking. Neither was intel on the latest party, concert, theatrical production, or where to get fake student cards. We travelled together on weekends and breaks, and cross-pollinated our respective travel dreams.

These living arrangements were pivotal points in our ability to get on with others, and built a solid foundation for lifelong friendships that endure to this day.

6. It was a time of a political awakening

In 1972, the voting age in Australia was 21. By the time the federal election rolled around on December 2, 1972, the Aussies in our group were both eligible and eager to cast ballots in our first election. Voting at Australia House in London was a momentous occasion, on many levels.

It was an exciting time, politically. After 23 years of successive Liberal-Country Party governments, the possibility of change was in the wind. The charismatic leader of the Labor Party, Gough Whitlam, outlined a reformist platform that included extricating Australia from the ‘war of intervention in Vietnam,’ abolishing conscription, providing tuition-free university education, establishing a universal health insurance system, pursuing land rights for indigenous Australians, and eliminating the remaining vestiges of the White Australia policy.

These, and others, were initiatives that appealed to us, and fronting up to Australia House to cast our ballots felt like we could actually have a role in their implementation. When the Labor Party won the election, it felt as though our votes had single-handedly swept our party of choice into government. It was the first and last time I voted in an Australian election, but It was a political awakening. I realized the importance of familiarizing myself with the issues, and the power of my vote.

7. Travel plans took time to unfold

When travel was actually booked, with no internet we relied on travel agents, booking agents, brochures, and postal mail.

It sometimes required physically presenting oneself to get the necessary information. When travelling through Central Türkiye on the way to Iran in November ’73, we encountered temperatures so brutal that continuing on the motorcycle was out of the question. The sound of a train in the distance offered a glimmer of hope that an alternative might be possible. Obtaining the schedule and information on whether or not the bike could be carried as baggage required a 70-kilometre ride from Göreme to Kayseri to find out that the next eastbound train would pass through Kayseri the following day.

8. Visas took time to get

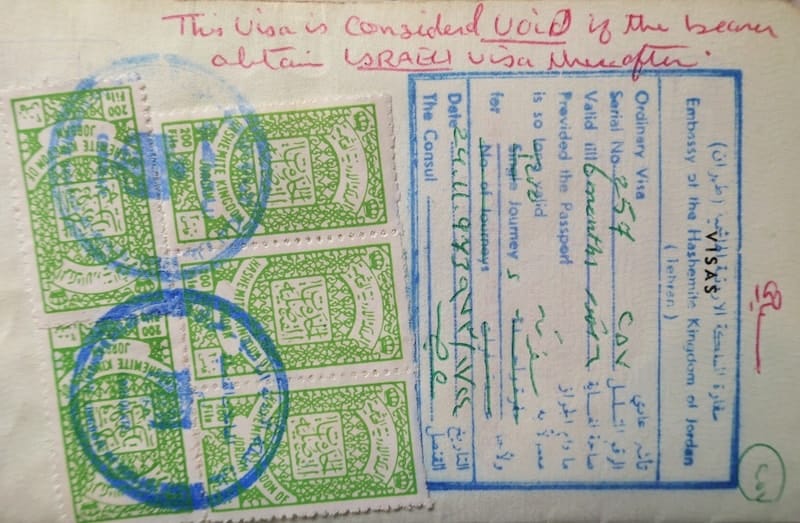

Forget about showing up at the border of some countries and gaining entry. And e-Visas were decades away. Lining up visas took months of planning, especially for extended periods of travel. We’d have to take our passports to an embassy, consulate, or diplomatic mission, or mail them in and wait for them to be returned.

I recall being the envy of other passengers with my Mexico and US visas. By the time the SS Australis docked in Acapulco, it had been 20, 18, or 16 days since passengers had boarded in Auckland, Sydney, and Melbourne respectively. I remember a cheesy ‘Miss Australis’ beauty pageant when contestants were asked about their life goals. The response “To get off this bloody ship!” resonated with many folks. I was thankful my friend Kris and I had planned to disembark in Acapulco and reboard in Fort Lauderdale seven days later. Had we not taken our passports to the US consulate in our home city of Brisbane, or mailed them to the Mexican Embassy in Sydney, this wouldn’t have been possible.

9. Mass tourism didn’t exist

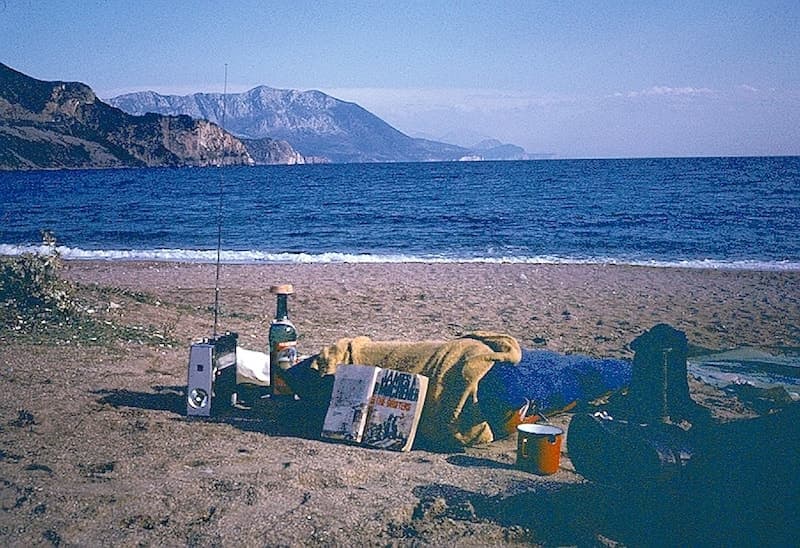

A beautiful beach was more likely to be deserted or have a few Kombi vans parked on the foreshore. My most prominent memories concern beaches along the stunning Adriatic coast of the former Yugoslavia, and sleepy coastal villages scattered along the southern coast of Türkiye. They were places to free camp for a few days, wash and air out clothes and sleeping bags, hang out with other travellers, and devour several chapters of a recently acquired novel. Today, they’re more likely to be dominated by resorts with access limited to paying guests.

I don’t recall sharing places with crowds, except in Munich at the 1972 Olympics and the ’72 and ’73 Oktoberfests. Today’s popular tourist spots such as Ephesus in Türkiye, Auschwitz in Poland, or Petra in Jordan attracted very few visitors.

At Ephesus, the night watchman, Hüseyin Sömen sprayed our tent pitched at the gates to discourage what we presumed would be an influx of insects during the night. He extended an invitation for us to join him in his tiny hut for tea and snacks. We didn’t share a common language but it didn’t matter as we somehow managed to chat for three hours. The next day, Hüseyin gave us a private tour of the archeological site in Turkish and German. We didn’t understand either; human kindness, generosity, and his pride in Ephesus we did.

At Auschwitz in 1973, we virtually had the place to ourselves. In fact, when leaving, we asked about a spot to camp and the attendant indicated we could pitch our tent in the parking lot. Today, the concentration camp memorial is so popular that there’s an online reservation system to control the number of visitors.

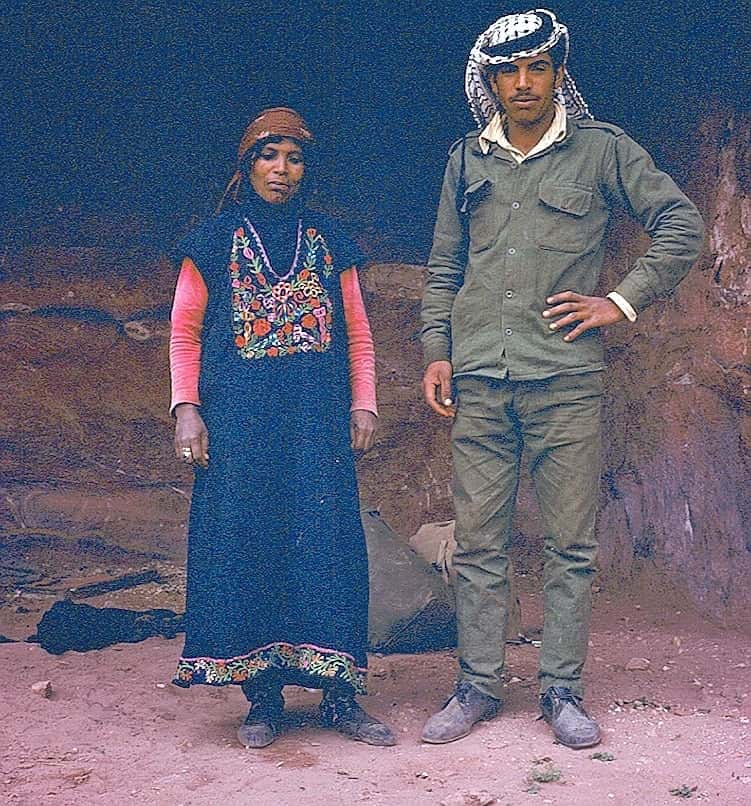

Petra? There was no entrance fee and very few tourists. I was hitchhiking with Hans, a German traveller I met at a hostel in Amman. In Petra, Bedouin tribes inhabited the area, living in caves or tents woven from goats’ hair. We were befriended by Ishmael, a young B’doul Bedouin about our age who took us to his family’s cave for supper cooked over a fire fuelled with camel dung and sticks. He guided us to far-reaching sites, showed us a cave where we could sleep and enjoy several pleasurable hours with him and a friend over tea and conversation.

When Petra became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the mid-1980s, the Bedu were relocated to the resettlement village of Umm Sayhoon. Today, their presence in Petra is most visible as tour operators or merchants selling souvenirs to tourists.

10. Paper plane tickets were the norm

We guarded those suckers like we did our passports. Lose them and you were in trouble. They consisted of several sheets of red carbon copies. Each page was ripped off with each soon-to-be-completed flight segment.

I cringe at the recollection, but there was the time I’d left our tickets at home, 550 kilometres away. It was during the Christmas break from teaching in the Canadian North. Thank goodness a helpful Air Canada agent was gripped with the Christmas spirit. She pulled out all stops to drum up replacement tickets to see us from Saskatchewan to Nova Scotia and back.

Oh, and planes had the ludicrous arrangement of smoking and non-smoking sections. The near-universal ban on smoking on airlines was two decades away.

11. Not all ferries were the roll-on-roll-off variety

It would be a strange concept today, but not all vehicular ferries provided the option to drive on and drive off. Loading and unloading involved vehicles’ being unloaded over the side in a sling.

In 1973, the ferry across the Irish Sea from Wales to Ireland unloaded our Kombi in this way. The TS Leda across the North Sea from Tynemouth to Bergen used a similar process to unload our motorcycle a few months later.

12. Travel guides were limited

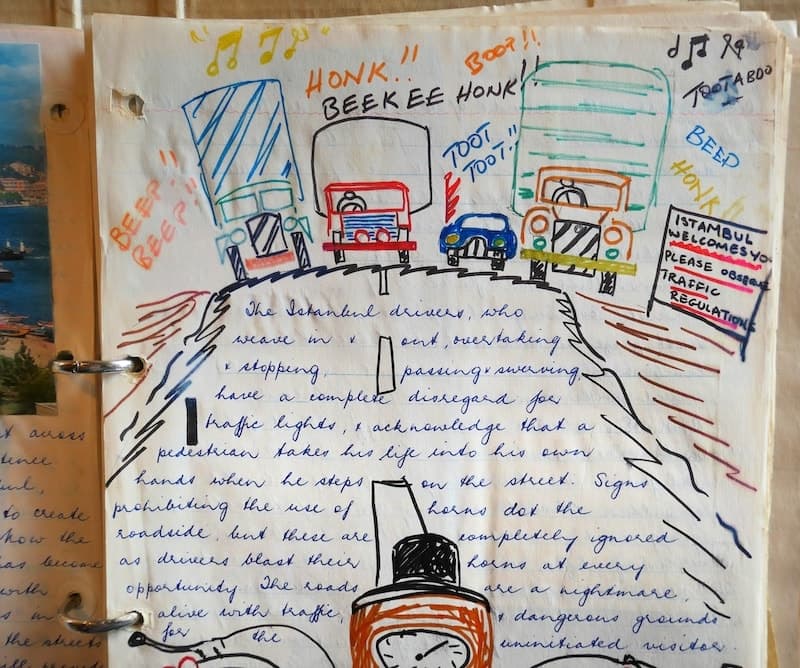

Europe on 5 Dollars a Day was our bible. By the time we reached Istanbul, travel guides had dried up and we relied on the recommendations of other travellers. Hanging out at The Pudding Shop and regularly scouring the notice board helped shape onward plans.

Or, we’d borrow whatever materials and pamphlets other travellers happened to have and make notes on the highlights. At an Istanbul campsite in ’73, I recall poring over a collection of borrowed resources on Asian Türkiye by candlelight.

Or we relied almost exclusively on printed maps. While in Tehran, we decided to spend a few days beside the Caspian Sea. The map showed a great body of water 200 kilometres away and the roads to get there. It was a simple matter of pointing the motorcycle north and we were on our way. No planning, no research, and no idea of what we’d encounter. It was a simple decision pulsing with grand possibilities. It was much the same when we decided to ride to the Persian Gulf with the map showing Esfahan, Persepolis, and Shiraz along the way. No research except from what we’d gleaned from talking to others, and what a glorious travel experience it was.

13. Plans were loose and changeable

We’d have a rough idea of where we were heading and how long it might take to get there. Our vehicles were acquired cheaply, usually from travellers who were heading home and looking for a quick way to unload what they couldn’t take on a plane. As a result, breakdowns were frequent.

At the end of the ’72 Oktoberfest, I joined two friends, Jo and Rhyll, for a spur-of-the-moment decision to drive from Munich to Istanbul. Our £30 purchase of a Kombi got us across the border into Austria before it succumbed to the negligence of its owners who failed to check the oil level of the engine.

All our wheels had a name; this short-lived one was called ‘Sebastian,’ a moniker that came with the registration papers.

The demise of Sebastian necessitated hitchhiking back to Munich for a more expensive £90 investment in a second van. Regular checks of the oil and a healthy dose of good fortune saw us to Istanbul and back to London to find work over the winter. This diehard returned to Europe and the USSR the following year before she gave up the ghost in Rome. She was called ‘Fanny.’

When hitchhiking, the availability of rides sometimes determined the destination. From the ferry port of Limassol in Cyprus, we chose the side of the road with the most traffic. I was hitchhiking with Rosalie from Vancouver, another kibbutz volunteer. It worked to our advantage, and led to a few nights’ sleeping on the Six Mile Beach near Kyrenia. It was there we heard of two job opportunities as ‘bar, grill room, and swimming pool attendants’ at a family-run business on the northern coast.

It overlooked the quaint former Greek Cypriot village of Orga, transformed into the Turkish Cypriot village of Kayalar following the 1974 Turkish invasion. Rosalie and I scored the jobs, and stayed in a room above the house of the President of the village who was also the barber. As a result, our predicted 10-day stay on the island extended to two months, ending a few weeks before the invasion.

From a chance roadside meeting with Iranian Ali Mohammadi on the outskirts of Istanbul in ’73, we replaced the plan to visit what was now war-torn Israel with three months in Iran. This was during the Shah monarchy, before the Islamic Revolution of ’79. Visas were easy to obtain, and westerners were welcome. Iranians stopped us on the streets, eager to engage us in conversation and practise their English.

When presented with the opportunity to trade our motorcycle in Iran for three Persian carpets, we grabbed it and said goodbye to our cantankerous two-wheeled friend ‘Ernie.’

All this to say, there were no commitments associated with employment, home ownership, or family obligations. Our choices were primarily driven by how far our meagre savings could take us. Financial security and planning for retirement weren’t on the agenda. We were in our early twenties; we lived for the moment and left those kinds of mature choices for later.

14. Travelling companions were collected along the way

Safety, finances, companionship, and convenience influenced the selection of travelling companions. For some, romance was part of the picture. Decisions to travel together emerged from conversations in a London flat, hostel common room, kibbutz dining room, or roadside encounter.

E-books and audiobooks were decades away. Printed books were heavy, so there were limits on what we carried. Novels were traded with other travellers. Only those worthy enough to earn a strong recommendation made the cut.

I remember my excitement at discovering the historical fiction of Leon Uris. It inspired future travel. Uris’ deep research provided a rich historical context for many of the places we yearned to visit. Exodus was an impetus for a trip to Israel and Palestine, and Mila 18 to the site of the Warsaw Ghetto. Serendipity intervened several months later when I walked into an office in Tel Aviv to volunteer to live and work on a kibbutz. I was sent to Kibbutz Yad Mordechai, dedicated to Mordechai Anielewicz, the young commander of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Book trades came full circle to forge meaningful connections through the transformative experience of travel.

16. The UNESCO World Heritage List didn’t exist

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) maintains a list of sites designated as having ‘outstanding universal value’ under the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and National Heritage. While adopted by UNESCO in 1972, it wouldn’t be until 1978 that the first World Heritage Site (Galápagos Islands) was inscribed.

The reasons for listing a property are what attract millions of tourists to the inscribed locations year after year. Until the list was created, sites received less exposure and fewer funds. Some never made it into travel guides (where they existed) or into conversations between travellers. The latter was our main source of intel when travelling through Central Türkiye in 1973.

Case in point, the underground city of Derinkuyu wasn’t on our radar. It joined the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1979. The first Lonely Planet Guide, “Across Asia on the Cheap” published in 1973, summarized Türkiye in 10 pages, with Derinkuyu mentioned under the reference, “At a number of sites are the remains of underground cities…). Some in-the-know tour companies on the Overland Route included a stop in Derinkuyu that bears little resemblance to the tourist attraction it is today.

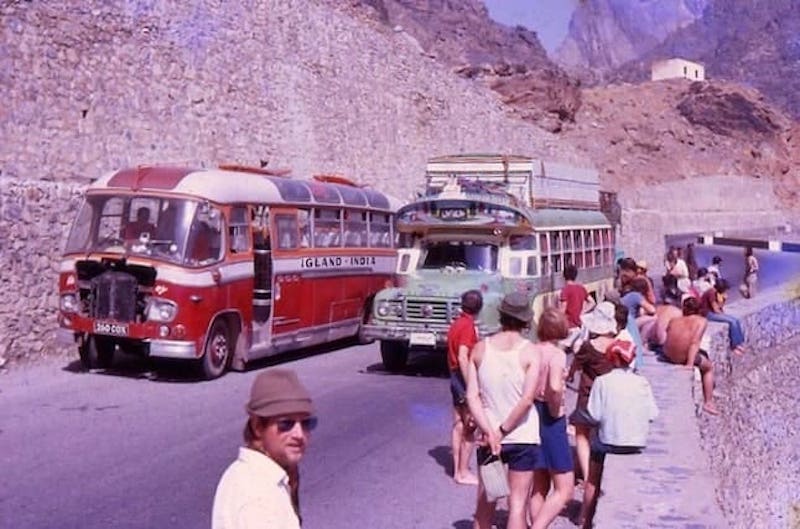

Credit: Pete Morey, 1971

Credit: Pete Morey, 1971

17. Travel quashed preconceived ideas

Something that hasn’t changed is that travel unlocked minds and opened up new ways of thinking and seeing. It expanded one’s worldview. One early youthful revelation concerned the countries that were the major sources of Australia’s post-war immigration boom. Greece, Italy, and Yugoslavia stand out in particular. I grew up believing that Australia was the greatest country on earth, and assumed these contributing countries had so many blemishes that they warranted leaving.

What I found in each was stunningly beautiful scenery, a rich cultural heritage, amazing food, fantastic architecture, history oozing around every corner, and friendly, welcoming people. It didn’t take long to realize that Australia, or no country for that matter, had a right to claim to be the greatest of them all.

18. Tea and biscuits were staples

Conversations with other travellers invariably involved a cup of tea. We’d stop by a Kombi with German plates, a motorcycle with Italian ones, or an old London taxi sporting a GB or NZ sticker. It was an excuse for morning or afternoon tea, even if the clock indicated otherwise.

The same held true for merchants, nomads, and other residents in Türkiye, Jordan, and Iran. Hospitality and tea were integral elements of social interaction and we enjoyed many positive encounters as a result.

After pitching the tent and cobbling together supper, we’d wile away the hours with our neighbours and new friends over tea and biscuits. Beer and wine were luxuries in most countries; tea we could afford.

19. Conversation was key

Conversation was essential to gathering intel about all things travel. We knew how to ask questions, a skill I find lacking in today’s world. We were curious about where people were from, their previous adventures, and where they were headed. Questions unlocked what we had in common. There was no internet to distract or inspire us; we relied on questions, conversation, and storytelling to forge relationships and shape our travel dreams.

20. Several address books were filled

Contact information was stored in small address books, essential accessories for the regular postcard-writing activity. Names and addresses were collected along the way so our address books filled up quickly, with multiple amendments for friends on the move.

21. Country-counting wasn’t a thing

I often see questions in Facebook groups from travellers who are seeking guidance on ‘what counts’ as the right to include a country in their ‘I’ve-been-to-X-countries’ claim. “If I have a two-hour airport layover, does it count as having visited that country?” I’ve never understood the motivation behind these types of questions or the need of some people to summarize their travels as a statistical statement.

If country-counting was a thing in the 1970s, I wasn’t aware of it. There were no discussions of what criteria needed to be met for a country to ‘count,’ or references to how many countries could be ‘done’ by travelling overland from London to wherever using a particular route. It was the same with continents. When we crossed the Dardanelles into Asian Türkiye, it felt exciting to be venturing into the unknown but there was no mention of adding another continent to our non-existent list.

22. A tour with no guarantees of reaching the destination

Several tour companies plied the ‘hippie trail’ until the late 70s. It was an alternative form of tourism marked by cheap fares, old buses, frequent breakdowns, and flexible schedules. Routes varied, but most tours started in Western Europe and ended in India or Nepal. My friend, Pete Morey, travelled from London to New Delhi with The Overlanders in 1971. The trip was expected to take seven weeks (if you were lucky) and folks were advised prior to booking that there were no guarantees of completing the trip. If the bus had a serious breakdown, passengers were expected to find their own way.

Credit: Pete Morey, 1971

Credit: Pete Morey, 1971

23. We survived on a limited travel budget

Des, one of my travelling companions, described his travel budget as being smaller than a gnat’s nostril. There was no margin for the extravagances of guided tours, expensive experiences, eating in restaurants, or exploring the bar scene. Munich’s Oktoberfest was the exception. There was ample room in the budget, if not our constitution, for those one-litre steins of magnificent German lager.

Accommodation costs were minimal. The Kombi was parked in back streets, parks, fields, or on beaches until the prospect of hot showers lured us into campgrounds.

While travelling by motorcycle, in cities we stayed in campgrounds. Outside urban areas, camp was set up in forests, amongst scrub, in caves, on beaches, or wherever we could pitch a tent or sleep under the stars. In Türkiye near Denizli, we slept under a bridge, and in a tomb at Pamukkale. In the Sinai at Eilat, we commandeered one of the coveted clumps of palm trees that provided ample protection from the elements. In the freezing temperatures near Persepolis in Iran, the tent was more valuable as a blanket.

24. We survived without Facebook and Instagram

Social media didn’t exist. In a way, it was a blessing. We weren’t constantly plugged in to a home we’d intentionally left behind. There were no ‘instagrammable’ images beckoning us to follow the hordes to sites of mass tourism, or a digital universe to stifle our capacity for independent discovery. Destinations weren’t shared with influencers or ordinary travellers who packed or rented fashionable wardrobes for capturing self-promoting photographs beside iconic landmarks.

Selfie sticks didn’t exist so we didn’t have to witness people taking unnecessary risks for extreme selfies or ‘the perfect shot’ to garner as many likes as possible. If travel was regarded as a competition or a checklist in the ’70s, social media wasn’t a platform to promote it. And hunting down Wi-Fi to access it was an albatross several decades into the future.

I’m pleased our generation didn’t have to think about the unchecked power of social media, and whether or not we had to succumb to the pressure of using it to influence or profile our travels.

25. Water wasn’t packaged in bottles

We escaped one of the greatest cons of the century, and as a result, didn’t have to encounter an endless supply of discarded water bottles along the way.

Water was available from taps, fountains, and natural places. In Yugoslavia, just outside Titograd, I recall going in search of water from our camping spot amongst scrub. Finding access to the stream beside the road turned out to be an exercise in futility. Stumbling across a house and pointing to my empty water container to kids playing in the yard brought me to a couple of guys drinking beer out back. Biscuits, cheese, beer, interesting conversation without a common language, and a full water container later, I was on my way. All without contributing to the scourge of discarded plastic bottles.

26. Poste Restante figured prominently in our plans

I remember the joy of receiving a fistful of correspondence from home or our ‘wanderlusting’ friends. Those were the days when mail addressed to a person’s name, Poste Restante, name of city/town and country, was delivered to the main post office. The Poste Restante was also a meeting place. In Munich in ’73, it was a place for a scattered group of friends to meet at several specific days and times on the eve of Oktoberfest.

Mail was the only way to confirm arrangements or send regrets. Returning daily for an entire week to the post office in Kyrenia to find out when my friends would arrive was filled with anticipation and excitement. Eventually, Graham and Rhyll’s postcard arrived with the news they’d changed plans and were bypassing Cyprus.

27. Aerogrammes and postcards were communication staples

Do aerogrammes still exist? They were blue with six panels, including two for addresses, and packed with news. There was no spell check, so crafting them took time. I can still recall the taste of the glue on the flaps.

Does anyone write postcards today? I don’t. But back then, postcards were the communication of choice on the road. We’d grab a bulk purchase deal, and head to the post office for stamps. Writing and mailing them took coordination. Time would be carved out to find a comfortable place to write quick summaries. They’d have to be mailed while the postage stamps were still valid, before crossing a border. Today, my handwriting wouldn’t cope after decades of tapping away at a laptop or phone/tablet keyboard.

28. Telephone calls were rare

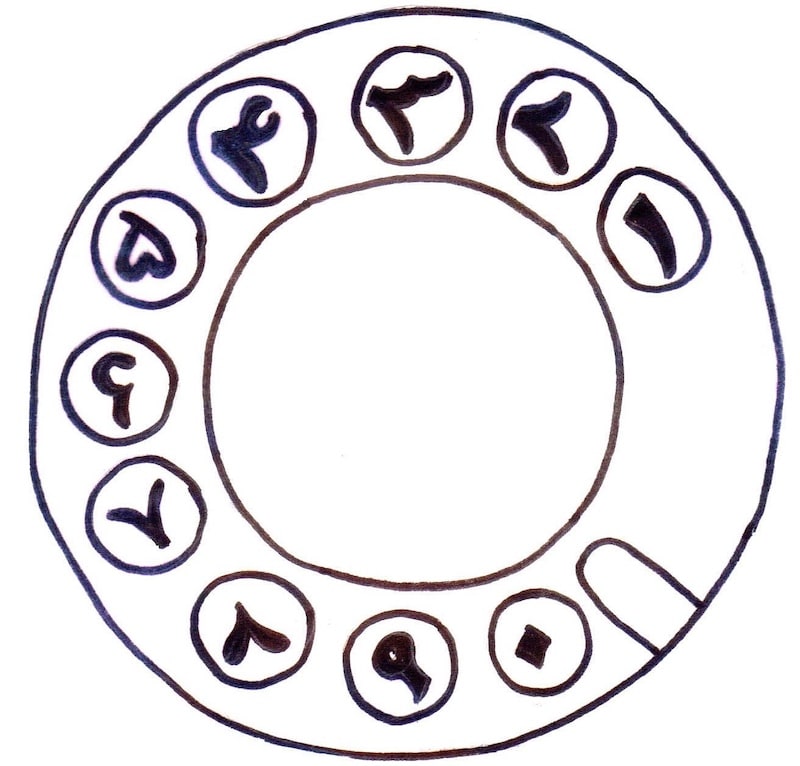

Using a telephone was costly, and call quality was questionable.

Some systems weren’t intuitive, and instructions in a foreign language unhelpful. A call to an international school in Tehran to suss out job prospects was made more complicated by the unfamiliar dial. Nevertheless, it was so interesting that it warranted reproduction in my journal.

29. Passport stamps were important

Passport pages filled quickly with visas and entry and exit stamps. They were as important for where we’d been as for where we were headed.

A visa or stamp of a previously visited country could raise flags for officials. My Israeli arrival stamp posed a serious problem for Jordanian police, with threatened deportation after crossing through the militarized zone at the Allenby Bridge. I should have known better. The Jordanian visa had a clear annotation, “This visa is considered VOID if the bearer obtains ISRAELI visa thereafter.” Technically speaking, it wasn’t an Israeli visa but semantics meant very little considering the significant and deeply rooted political context. In the end, I was granted permission to stay in Jordan and return to the West Bank by the way I came.

30. A divided Europe

The Cold War led to a divided Europe and fortified borders. Travelling behind the Iron Curtain was complicated. It required multiple visas, compulsory currency exchanges, and rules on where we could cross or spend overnight.

In 2013, I cycled through four countries on the Danube Waltz by Bike and Boat tour. Were it not for the boarded-up buildings and weeds growing in the traffic lanes of an old border crossing, it would have been difficult to identify at which point we crossed from Austria into Slovakia. There was no need to carry passports on our bike and boat journey across four countries. For someone who had passed through these countries in the ‘70s, it was quite the revelation.

31. A divided Germany

In 1972, visiting Berlin by road involved crossing from West Germany into East Germany (German Democratic Republic or GDR/DDR). Reaching West Berlin from the Helmstedt-Marienborn crossing required passing through the 180-kilometre GDR corridor. Armed guards, boom gates, and observation towers were ever-present reminders of a strong police and military presence. While in transit through the corridor, it was forbidden to take photographs or deviate from the highway. Stopping was permitted only in designated parkways.

We were stopped nine times by GDR authorities for vehicle and passport checks at various points along the corridor.

A divided Berlin was another eye-opener. Beside Checkpoint Charlie, the strip of no-man’s land was a sombre reminder of Germans who had lost their lives trying to cross. The dilapidated buildings on both sides of the wall seemed to be waiting for a time when urban regeneration could restore Berlin to its former glory, without a wall separating the two pulsating hearts aching to be one.

32. Taking photographs required constraint

Film was expensive, and getting it developed was costly. Frugality was key when deciding whether or not to take a photograph. It cost money to find out if we had a winner or a dud, long after we’d visited a place. Quality of the better photographs was poor compared to the digital versions of today. It was virtually impossible to take a selfie, and besides, film and processing cost far too much to waste on self-indulgent narcissism.

Why did we take all those slides/transparencies? So we could bore people with a slide show after the trip? Whatever the reason, I have a sizable collection. I invested in a slide scanner upon retirement and digitalized those that were somewhat recoverable.

33. The underground market expanded travel budgets

Consumer goods and stable currencies were in demand in certain countries.

At a time when denim jeans were standard wear for young people in the West, the ideological view in the USSR was that Western fashion undermined Communist ideals. Nevertheless, young Russians were keen to get their hands on a coveted pair of Levi’s or Wranglers. Jeans weren’t manufactured behind the Iron Curtain until 1975. East Germany produced brands that couldn’t match the quality of those of the West. In the 1970s, Westerners passing through the USSR were offered exorbitant prices for the jeans they were wearing or carrying. Many young travellers counted on these underground-market transactions to expand their travel budgets.

In the Eastern Bloc, official exchange rates were much lower than those in the West, or available when exchanging currency in the underground market. For example, until the reunification of Germany, there were two separate German currencies. The East German government valued the East German mark and West German Deutsche Mark at parity. In West Berlin, it was possible to purchase East German mark at 4:1 but it was illegal to import them. Finding a way to hide legally obtained East German mark made travel in East Germany more affordable. In Warsaw, Poland, I was offered 26 złotych for one Deutsche Mark (DM) by a young street trader. I changed DM 50 and the 1300 złotych (less than £8) bought a warm jacket and boots, and a pair of woollen socks.

34. For the most part, airport security didn’t exist

My first brush with airport security was in Istanbul for my El-Al flight to Tel Aviv in 1974. Hijacking had emerged as a political weapon with serious repercussions for travellers. The deadly terrorist attack on Israeli athletes and officials at the Munich Olympics in 1972 had significantly raised the bar on security for El-Al as an airline, and all flights into Israel.

But security screening was targetted. In Istanbul, Des walked on the plane bound for London with no obvious security measures in place. I, on the other hand, was subjected to interrogation, frisking, and a painstaking examination of everything in my bag. It was so alien to anything I’d experienced that it warranted several pages in my journal.

35. Jumping freight trains was possible

My train-hopping adventure started from an exit ramp in Vancouver with a wave accompanied by a flippant gesture with my hitchhiking thumb towards a worker on a passing freight train. His response signalled an invitation to come on board. It was all we needed to scurry across the field and jump on the slowly moving train. Several trains, a variety of freight cars, 24 hours later we reached Edmonton.

Jumping freight trains is illegal and dangerous. To ill-prepared, young adventurers with high risk-tolerance thresholds, it felt exciting. It was, and meeting interesting railway workers enriched the experience. Just before Jasper, we were invited into a caboose to warm up and share conversation and stew with two engineers. One of them was a former RCAF pilot who’d crash-landed in France during World War II, and from their many decades of railroad experience they regaled us with stories. So it was with regret we had to quickly grab our gear at their announcement that our next train was just leaving the Jasper rail yards for Edmonton.

I would speculate that today, security measures would be more stringent and railway workers more constrained by company policies. Besides, the risks of financial penalties, imprisonment, and personal injury aren’t worth it. Back in the ’70s, our youthful ignorance and naivety didn’t give these considerations a second thought.

36. We were out of touch with world news

We relied on word of mouth, or the headlines of English language newspapers. For the most part, we were oblivious to what significant events were happening around the world.

Radio broadcasts kept us informed when we found a working radio with reception. In 1973, Des and I bought a shortwave radio in Munich that we planned to sell or trade in Istanbul. It was on a beach in Yugoslavia that we learned of the Yom Kippur War. As we were on our way to Israel, the news captured our interest. That notwithstanding, the conflict had all the elements of a serious international crisis involving among others, the two nuclear superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union. From that moment, we became news junkies tuned to the BBC over the days ahead.

37. Travellers’ cheques came with challenges

We didn’t live on credit or use credit or debit cards. ATMs didn’t exist. Travellers’ cheques were safer than cash, but not as convenient. Our motorcycle barely made it to a gas station in Türkiye after several attempts to find a vendor who’d accept them. I think we made the last few kilometres on fumes and downhill cruising.

38. Journalling was a daily event

With retirement, I enjoyed dusting off my collection of diaries and reading the musings of my twenty-something self.

The earlier diaries were mostly in cheap exercise books. I had a penchant for recording the mundane, such as what we ate and when we found a hot shower. The later ones were more interesting, with dialogue, lame attempts at poetry, and more descriptive accounts of people and places. Investing in glue and scissors for clippings and memorabilia made journalling more enjoyable, and drawing materials facilitated my ability to tap into the talent of travelling companions.

39. Music wasn’t accessible on the road

In the early ’70s, compact discs (CDs) were still two decades away. Cassettes had emerged as a more compact alternative to LPs, and our preferred format for prerecorded music. Portable players were large and bulky; the first Sony Walkman was released in 1979.

So our favourite music wasn’t something we listened to on the move. That had to wait until our return to London, or wherever we’d find work to fund the next travel adventure.

I was fortunate to share digs with some talented musicians. Steve showed me how to play a few chords on a guitar, and Annette introduced me to the music of Gordon Lightfoot, among others. Ralph McTell’s Streets of London became a perennial favourite, if not a signature tune of our ‘London 1972’ gang.

Tickets to live concerts were affordable. They weren’t extravagant productions involving dancers, elaborate lighting, special effects, and mega screens. In fact, I recall that Ralph McTell (or perhaps it was Don McLean) was accompanied on stage with a bass player — just the two of them. I saw Leonard Cohen at the Royal Albert Hall, Carole King at the Hammersmith Odeon, Joni Mitchell and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young at Wembley Stadium, and Elton John at a rinky dinky picture theatre not far from our Finsbury Park flat. I enjoyed performances of so many of these icons and more, at what feels like a fraction of the price of today’s concerts.

Another thing that hasn’t changed relates to the memories a particular song evokes. It takes us back to a different time and place. For me, this is the case with Don McLean’s American Pie released in November 1971. On reaching Houston in January 1972, we discovered it as a huge hit. By the time we reached London the following month, it had reached the top of the UK charts. Under our Finsbury Park flat, The Brownswood Park Tavern played it incessantly well into the night. Whenever I hear American Pie today, those recollections surface.

40. Lifelong friendships were formed

Friendships forged on the SS Australis have endured to this day. Our regular reunions in either New Zealand or Australia attract two-dozen or so friends accumulated during those earlier travels, with smaller get togethers in between.

Hugs, conversation, laughter, and camaraderie dominate each gathering, and the years melt away as we piece together the rich memories of our youth.

Which is better… then or now?

Was travel back then better? Do I prefer travel in my seventies compared to that of my twenties? There’s no definitive answer to either question. It’s just different.

But, I have to admit; there are things about the ‘old days’ I miss. And, there are things I don’t. My memories are sprinkled with both.

I was a member of a privileged generation. Race and youth worked to our advantage. That didn’t include the 20-year-old Australian men whose birthdays were drawn for conscription into ‘national service’ and a free trip to Vietnam. For the rest of us, travel was within reach and jobs were plentiful. And, for the most part, they were unionized jobs with decent benefits and working conditions.

What do I miss most about travelling in my twenties? It felt safer. It probably wasn’t, but our youthful naivety and misplaced confidence in our invincibility led to risk-taking I wouldn’t consider today. Along the same lines, what few material possessions I had weren’t worth much, so very little was invested in keeping them secure.

What do I like most about travelling today? It’s not without its pitfalls, but I love how technology makes travel easier. I can look up the weather, transportation, opening hours, and how to get from A to B at any time. I can book and pay for travel within minutes. I can satisfy my curiosity by looking up something on the fly. I can communicate in real time across borders at no cost, or in a foreign language with the help of Google Translate. The wealth of information on the internet makes me a better-prepared and better-informed traveller.

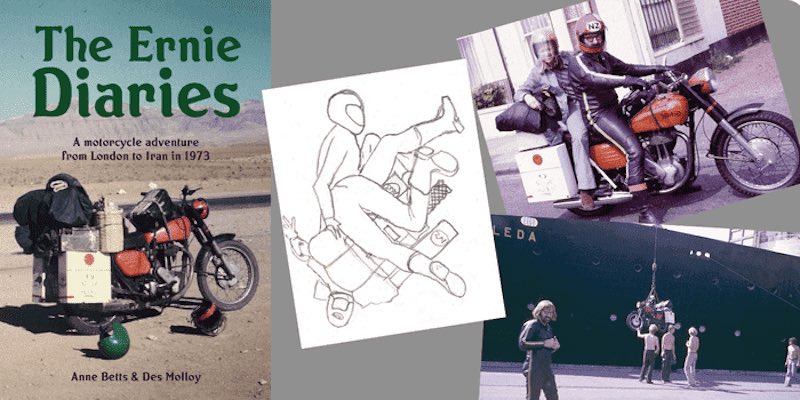

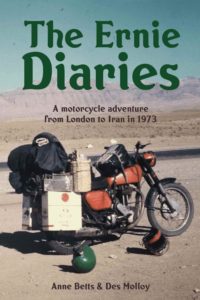

Might you be interested in more travel stories from this era? In 1973, I travelled with New Zealander Des Molloy for five months on an old 1957 Norton motorcycle. During the pandemic, we wrote a book on the experience: The Ernie Diaries: A motorcycle adventure from London to Iran in 1973.

If you enjoy reading chronicles of motorcycle travels, check out Des’s recent works. The Last Hurrah: From Beijing to Arnhem is available as a DVD and book package. No One Said It Would Be Easy: A youthful folly across Americas on old bikes describes an adventure in the late ’70s. Zen and the Last Hurrah follows in the wheel-tracks of Robert Pirsig’s ride across back-country USA. Check out Kahuku Publishing Collective for more information.

Also, here are a couple of related posts:

Care to pin for later?

That was a GREAT story!

Hitchhiking in the US in the summer of ’71 I remember Rod Stewart’s “Maggie May” on the radio of all those cars I got rides in, I remember that summer every time I hear that song…

I remember going with my parents to Europe in 1971 from Los Angeles – my mother worked for LA County and they used to offer flights from LAX to London for $200 on charter flights – BOAC. I was only 11 – I remember how rare it was to find people who had been to Europe. A hotel for 4 in London cost $20, before the chunnel you took the ferry to France. We went to Switzerland as well but unfortunately got in a car crash and my mom went to the hospital. I remember all the strange currencies and accents and it made such an impact upon. Now retired, I have over 60 countries under my belt and it all started with that family trip to Europe 50 plus years ago.

Fantastic writing. Brings back some memories using Frommer’s Europe on $10 a day. Used Eurail & Britrail passes & then walked into the visitor information centres for a BnB booking. Some dodgy lodgings in Italy & Vienna make me shudder today. Really loved the historic Youth Hostel buildings.

As you say the naivety of the young.

Mind you we’ve just had 3 weeks in Antarctica on the fantastic Australian ship the Greg Mortimer ( before lockdown).

I was on that remarkable voyage on Australis arriving in Rotterdam in February 1972. I stayed away for four years hitch-hiking all over Europe and North Africa and going back to Australia in 1975 via Greece, Turkey and the Middle East and Iran and India and Nepal and Thailand. Lots of adventures

I would like details of the March 2022 meeting in Australia of those passengers on Australis.

Great blog. Brought back memories of 5 months backpacking around Europe in 1981. By that time it was Frommer’s Europe on $20 per day. OK in Spain, Italy, Greece but very difficult on $20 in Scandinavia.

Have been back several times since then but by then could afford Hotels, B&Bs etc Even did a cruise in the Baltic last year.

One of the shared experiences from the early trip is the free or minimal admission charges to museums, Cathedrals etc. Not so now.

So once again, thanks for the memories. Can you believe we left school 54 years ago?

Bruce, I remember you. I recall your Dad was the groundskeeper at our high school. Correct? And you had a killer singng voice and an awesome band. Thanks for your comment. Perhaps I’ll see you at the next high school get together 50 to 60 years after those special times. Stay safe.

Great read, Anne! So many insights into 70s life even for those of us who didn’t travel much!

Hi Anne,

Amazing Article.

I am professional travel blogger. I never thought I would get travel tips so old. Here the travel guide of 1970 will increase our travel inspiration. I’m really lucky.

Thank You!!!

–Evie

Hello Anne, excellent article. That was life; I believe that at that time people were happier; everything seemed more natural.

Thank you for sharing these experiences!

Oh, my, what a wonderful story! I loved every minute of it. While I was fortunate to have lived in Germany in 1968–1971 with my family, and we traveled extensively, I longed to have been able to travel as you did. However, with my father footing the bill, we were able to stay in hotels and inns and all that. My favorite memory is our trip in 1971 through Germany, Jugoslavia and even Hungary (which involved four hours obtaining visas and having our entire vehicle examined, and the Hungarian soldiers confiscating my brother’s Sports Illustrated!). We encountered a school principal in Sopron who invited us to meet his family; we were given a tour of the town as celebrities almost–I doubt they saw many visitors. We traveled further through Austria and down to Italy, as my father’s work with DuPont was about over and we had to see it all. Fabulous to learn how others live and amazing that people are the same all over, aren’t they? Thanks for sharing your stories!

Hi Anne, loved your story, brought back many memories. I travelled from Oz to Europe on the Australis in 1969, home in 1970, back in 1973, home in 1974. Did you know there’s a Chandris/Australis facebook page with over 4,000 members? It’s called SS Australis Photos n Stories & Chandris Lines. Have you considered publishing your memories as a book? I did, as have a few other members in the Chandris group.

Sandy recently posted…PARIS (part 2)

Hi Sandy. Thanks for dropping by. Your book is downloading as I type. I skimmed the first page on your site and fell in love with your writing. I can’t wait to read your story. Unfortunately, my Australis diary isn’t much use except to describe the endless partying and how many breakfasts I missed. And missing the departure time in Suva and getting a ride to the Australia on a tugboat. Very embarrassing. Thankfully, my journalling improved and I’m currently co-writing a book describing 5 months travelling on a motorcycle with my NZ travel buddy. I’ll be returning to your site to soak up your memories, and visiting the Australis site as well. Thanks again.

Anne Betts recently posted…12 Ideas on what to include in a MacGyver kit for travellers

That was a GREAT story about the 1970s and now traveling. I really enjoy this blog, read about how they travel these time. All those things are not the same as a present scenario. Thanks for sharing with us!

I loved this nostalgic post! I was born in the 90s so my experience of travel hasn’t changed that much during my lifetime. I imagine in the 70s you made a much better connection with destinations when you had to rely on conversations and weren’t constantly connected to social media! I wish I could have experienced it! Thanks for sharing your stories!

This was such an interesting read! I always love reading about the past and how things have changed over the decades. I would love to see more posts like this from you! 🙂

I absolutely loved this post, thank you Anne! You have had so many adventures, I really enjoyed reading about them. Fascinating how much travel has changed over the decades. Not only are there so many more of us traveling, but you’ve highlighted how the ways in which we do so are different too. Your photos over the years really add a depth to the article too. I have been on many ferry rides but never like yours across the Irish Sea!

What an interesting look back at travel in he 1970s. I can’t imagine it taking 5 weeks by ship to Europe. On our last ship crossing it took 5 days! So strange that vaccination was a thing back then too. So many people seem to think the current vaccination requirement is “new”. And I can’t imagine not having the internet to do planning. And deal with changes as they come. But I am sure it was awesome to see great sites like Petra not swarmed with tourists. But then, so many people might not visit if they could not do it “for the gram”.

I loved reading this, definitely a very different time to travel, but I do remember even in the late nineties not having a cell phone when traveling, no Google maps to rely on, having to find an internet cafe to check email, and getting lost constantly by getting on an incorrect bus because you can’t check it out online in advance. Times are constantly changing, and while all times have their pros and cons it’s really interesting to think about how much technology is relied upon now, and how nice it would have been to truly switch off. I remember as a kid in the 80s that my parents would give me my camera and a 36 exposure film for my holiday and you had to have restraint. I feel like I take more photos now that I never look at than the selective few I had to take back then

Your post was so interesting! thanks for sharing Anne .

Great story to read! Thanks for sharing.

Such nostalgia! Thank you very much for your time and efforts. Your blog is so well written it felt as if I was back on the road (train, ferry, horse cart, motorcycle….). I had the pleasure (as an American) of meeting Australians everywhere- Earls Court, aboard ships, in the Canary Islands…. I just picked up Jules Vernes’ ” The Adventures of A Special Correspondent ” about travel across the Caucases to Pekin. I suspect that international travel in the 1970s more resembled that of the late 1800s and earlier 1900s than it would today. – John from Missoula, Montana

What a wonderful story, so well written, and brought back memories of my travel years from 71 to 74

I was on the Australis leaving Oz in Nov 71. My travel mate and myself left the ship in USA, purchased a Kombi and then drove all around the States and Canada. Your comment about the song American Pie was so poignant as we would be driving along with our small transistor at full volume with this song. Everytime I hear it now I am taken back.

In 1972 I travelled in an old bus with Sovtrek written in large letters the side and travelled through all the eastern cold war countries – Czech, Hungary, Romania, Ukraine, Russia. People were so friendly and it hurts watching the nightly Ukraine sufferings.

Thanks for posting your travels

Tony

Lovely to read this and hear about other people’s travels in all these various parts of the world. My travel experience from 1971-72 involved travelling overland to India from the UK and travelling and working in Nepal, India, and Bangladesh (newly liberated in 1971). Sometimes known as ‘the hippy trail’, this label has detracted from the actual experience of many of us. I was not a ‘hippy’. I was a recently qualified nurse and I worked as a volunteer in a hospital in Nepal and in India in the Bangladesh refugee camps of 1971. I travelled as well from North to South, from Nepal to Sri Lanka. In those days British subjects did not need a visa for India. I learnt, and have continued to learn since, about the history of colonialism. Forget the cliches about spiritual seeking in India so often associated with that era. That journey for me was a political awakening.

I’m insanely jealous. Travel has changed- and not for the best. I would give anything to have experience travel during this time. You are lucky to have had these opportunities and experiences.